Trollopes Bird Notes

March 2022

Click for Trollope's September 2021 notes

Satellites solve mysteries of incredible journeys

For nearly a hundred years, Cuckoos were regularly ringed in an attempt to discover where they spent the winter, but in all these years only a single bird was recovered, having been found dead in Cameroon. Thanks to satellite tagging we now know our birds overwinter in the Congo, using Cameroon only as a staging post.

Following the success of this tagging, Cuckoos were tagged near Beijing. The wintering areas of birds from China was a total mystery: was it south-east Asia, India or elsewhere? Amazingly, the birds were discovered to fly south to avoid the Himalayas before turning west to fly over/through India and then make the long crossing of the Indian Ocean to Somalia and then south to East Africa.

For nearly a hundred years, Cuckoos were regularly ringed in an attempt to discover where they spent the winter, but in all these years only a single bird was recovered, having been found dead in Cameroon. Thanks to satellite tagging we now know our birds overwinter in the Congo, using Cameroon only as a staging post.

Following the success of this tagging, Cuckoos were tagged near Beijing. The wintering areas of birds from China was a total mystery: was it south-east Asia, India or elsewhere? Amazingly, the birds were discovered to fly south to avoid the Himalayas before turning west to fly over/through India and then make the long crossing of the Indian Ocean to Somalia and then south to East Africa.

Tagging solved one of the great migration mysteries: how do Bar-tailed Godwits reach their wintering quarters in New Zealand from North America? What route do the birds take? Scientists had thought it impossible for the birds to carry enough fat reserves to make the 8,000-mile journey, but the scientists had got it wrong and the birds, indeed, complete the journey without stopping.

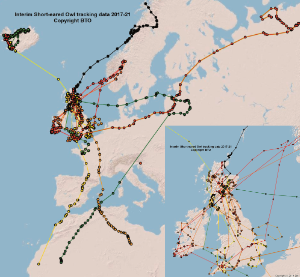

Tagging can also be used for purposes other than determining migration routes and wintering quarters. When I retired in the early 2000s I worked professionally for the British Trust for Ornithology, carrying out field work to help conserve farmland birds. When this project finished I was offered the chance to carry out field work in Scotland to learn more about why the Short-eared Owl, Asio flammeus, was in decline. The thought of being paid to walk the hills in Scotland for three months seemed very attractive, but sadly I had to decline due to many other commitments. A few years later, the BTO launched an appeal for funds to tag these birds, to which I gladly signed up, and every now and then I get progress reports.

The idea was to learn where the birds spend their time so that conservation plans could be put in place. The Short-eared Owl is one of the most widely distributed birds in the world, only absent in Antarctica and Australasia. Traditionally, birds in the UK were considered to be mostly partial migrants, leaving the highlands to winter in the southern UK, Southern Europe and North Africa but the new tracking data is showing that their movements are much more complex and variable. They are ground nesters, usually laying four to seven eggs, and sometimes more in high vole years. Their life span can be up to 12 years, though the new tracking data show that it is typically much less.

There have been two or three occasions in winter where I have seen them along the Rother valley near Newenden. Around the Kent coast in winter estuaries, a favoured habitat, there are usually between 30 and 90 birds recorded. The Isle of Sheppey is the best place to see them and in 2019 a pair remained to breed there.

The tagging of these birds has led to the discovery of some extraordinary and incredible journeys that these birds undertake. In 2018 a pair bred near Stirling in Scotland, and before the young were independent, the female left her mate to look after the chicks and flew to Norway to breed with another male. She returned to winter in Britain, initially to Ireland then Cornwall and finally Norfolk. In the spring of 2019, she flew in the direction of Norway but perished over the North Sea.

In Scotland she bred in mountain grassland and in Norway it was dwarf scrubland. The owls’ main food supply is small rodents, particularly short-tailed voles, but they will also take birds. In June 2020, two adult female birds were tagged on their nests on the Isle of Arran; one spent the subsequent winter in south-west England and in April/May of this year it travelled to the Pechora Delta in Northern Russia, 3,100km away, to breed. I wonder if this a world record for the greatest distance between breeding sites for any species?

Another adult female, tagged only kilometre away on Arran in the same year, travelled to Norway to breed the following year. In all, 25 birds have been tagged, most at their nest, and the closest that any of these birds has nested in the following season is 40km. The tracking of these birds has also revealed that they winter further south in Africa, reaching the depths of the desert of Western Sahara. When this project was initiated to try and determine where these owls bred and wintered, and then draw up some conservation measures, the researchers could never have realised how complex and wide-ranging the problem would be.

Charles Trollope cetetal@btinternet.com

Events